Музей космонавтики

- Opening hours

- Mon Closed

- Tue, Wed, Fri, Sun 10:00 — 19:00

- Thu, Sat 10:00 — 21:00

The Museum of Cosmonautics is one of the largest scientific and technical museums not only in Russia, but in the whole world: the museum's total area consists of more than three square kilometers, and it includes more than 98,000 exhibits in total.

We have chosen the 15 most iconic space artefacts that inspire visiting our museum.

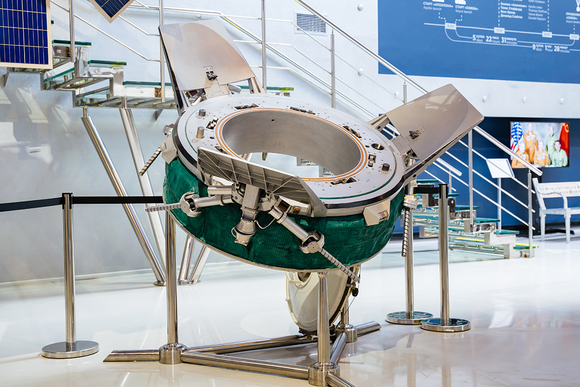

Spunik-1 was the first artificial satellite, and paved the way for the first cosmonaut and many scientific and technical achievements. Our museum, in which the first artificial satellite takes an honorable place, would not exist without Sputnik-1. On the 4th of October, 1957, this simply-constructed small sphere ushered in the “space” era in humanity’s history. Well-known throughout the world by its international name, Sputnik-1 recently added another point to its biography: Sputnik-1 became one of the symbols of the Football World Cup in Russia in the summer of 2018.

The museum also features the stuffed four-legged space heroes Belka and Strelka, and the genuine descent vehicle. This is the very vehicle in which the two brave dogs returned to Earth after their successful space flight on August 19th, 1960. As a reminder of the canine feat, damage, dents, and traces of a soft landing remain on the walls of the flown container.

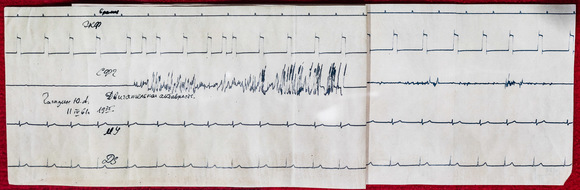

You can see how the heart of the world’s first cosmonaut was beating before launch on this unique document: an electrocardiogram taken from Yuri Gagarin on the evening of April 11th, 1961, less than 24 hours before his flight. Heart rhythms and other medical indicators were taken from Gagarin every four hours. According to the memoirs of professor and Doctor of Medical Science Ada Kotovskaya, who prepared the first cosmonauts for flight, “During the last check of the sensors, our recommendation was that Yuri was quiet, concentrated, and very serious. Occasionally, he sang couplets from songs that were popular at that time, but more often he was quiet. Four hours before the launch, (I have a shot of his EKG) it was clear that Yuri was worried. But who wouldn’t be worried! He could simply hold back his emotions.”

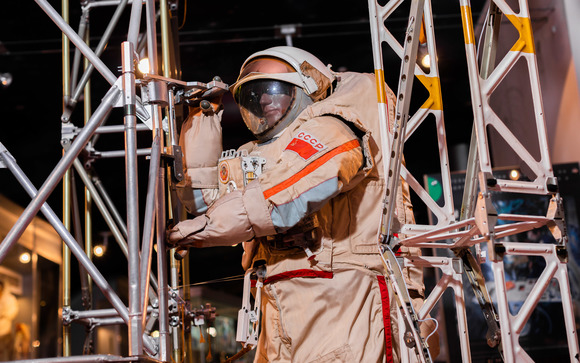

The worksuit of the first cosmonauts is different than the spacesuits sent to orbit today. Even then it was not simply clothes, but a sophisticated engineered construction with a ventilation system and life support system, designed to be used for 10 days. Yuri Gagarin, German Titov, Andrian Nickolaev, Pavel Popovich, Valeriy Vikovskiy and Valentina Tereshkova went to space in these spacesuits. For the latter, a special spacesuit was sewn for the female figure.

Mikhail Tikhonravov’s construction was the pioneering development of the Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (GIRD). Launched from a landfill in Nakhabino, the rocket had hybrid propellant (a mixture of rosin and gasoline), reached a height of 400 meters, and opened the era of Soviet rocketry. “The day August 17th, 1933 is undoubtedly significant in the life of GIRD and starting from this moment, Soviet rockets can fly over the Soviet Republic!” Sergey Korolev wrote shortly after for the information board.

One of the major exhibits of the museum’s collections is the full-scale spacecraft series “Soyuz.” Today, Soyuz is the primary “work horse” of the world of cosmonautics: since April 23, 1967, it has completed 133 successful piloted launches to orbiting stations “Salyut,” “Mir,” and the ISS. The spacecraft presented in the exhibition consists of three units: the living and instrumentation compartments and the genuine descent vehicle “Soyuz TMA4,” on which the Russian cosmonaut and record-holder Gennadiy Padalka launched and returned in 2004.

The "Mir" model is the most popular and most visited exhibit in the museum. Here, anyone can try on the “space” life: estimate the scale of the orbiting house, see the cosmonaut’s bedrooms and workspaces, dining table, and of course, bathroom (spoiler: it is quite familiar to terrestrial species).

This 14.5-meter-long construction was installed by cosmonauts Anatoly Artsebarsky and Sergey Krikalev on the “Kvant” module of the orbital station “Mir” in July 1991. In addition to its technical achievements -- “Sofora” was intended for installation on the top link of the outboard propulsion system (OPS) -- this unique construction went down in history as the mast for the final and tallest raised flag of the USSR, which was in space until March 1992.

This vehicle – in accordance with the creator’s idea – helped cosmonauts with repairs and scientific work in open space and played one of the most important “Cold War” roles in space. “The cosmonaut’s vehicle” was an autonomous space machine with jet engines, a power supply system, control and communication systems, and a special safety cable, and was also considered for combat application. For example, USSR cosmonauts could use it to deactivate and incapacitate enemy satellites.

Lunokhod-1 was the first autonomous self-propelled vehicle on the surface of another celestial body. It travelled on the Moon for 10.5 kilometers and became one more triumph of Soviet science. This 8-wheeled scientific laboratory, the size of the Russian car “Zhiguli,” completed numerous research missions and experiments, as well as a practical mission – finding the landing place for the piloted Soviet mission to the Moon.

The unique control panel, which managed the first “Lunokhod” mission in 1970-1971, was passed on to the museum by Vyacheslav Georgievich Dovgan, the driving operator of the “Lunokhod-1” and “Lunokhod-2.”

This is the spacesuit of Michael Collins, one of the members of "Apollo 11," the first piloted mission to the Moon,” and the pilot of the command and service module “Columbia." Collins, unlike the other two astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, did not walk on the Moon’s surface. However, he went down in history as the first human to make two spacewalks.

This spacesuit, which has visited the Moon’s orbit, was gifted to the museum by the director and main constructor of the Research and Development Production Enterprise "Zvezda," Guy Ilyich Severin.

On December 1971, the Earth saw how the surface of Red planet looks for the first time when Mars-3 transferred several pictures via video signal. The automatic scientific station safely landed on another planet, and deposited the PrOP-M machine -- a walking device for evaluating Martian soil passability -- on the surface of Mars for the first time. The machine didn’t meet the Martians, but transferred valuable information about the composition and structure of Mars’ atmosphere, temperature, and terrain.

This container completed the first ever automatic delivery of Moon soil to the Earth - one more achievement of Soviet science and technology. In 1971, the expedition brought back from the Moon 101 grams of regolith, taken not far from the Sea of Abundance. The mission confirmed the Main Constructor’s words - the surface of the Earth’s satellite was hard and the same age as bazalt on our planet. 20 pieces of Moon soil were delivered to the Earth on the space vehicle “Luna-16," which you can also meet in our museum.

The first joint flight of the two superpowers was preceded by prolonged negotiations, during which one of the critical questions was the compatibility of the docking modules of the two spacecraft. The Soviet experts first proposed their well-tested and reliable Docking and Internal Transfer System (DITS). DITS was a gendered design that combined an extended probe with a corresponding cone-shaped drogue. It required each spacecraft to play a specific “male” or “female” role that could not be reversed in the docking process. After prolonged negotiations, engineer Vladimir Syromyatnikov proposed APAS, an androgenous solution that was accepted by both sides. According to this system, each mating module would be equipped with three guide fingers that simultaneously played the role of both the probe and the drogue. The APAS-75 variation enabled the Soviet "Soyuz" to dock with the American "Apollo" in orbit, and the crews of the ships to meet over the planet. Subsequently modified versions of APAS were used at the “Mir” space station and the ISS for Space Shuttle docking.

"Buran" was the final resounding triumph of the Soviet Union, a “Russian miracle” and our answer to the American Space Shuttle program. “Buran,” unlike the American Space Shuttle, accounted for an emergency rescue crew. The spaceship-monoplane was designed for 100 flights. But, due to the intense flight environment created by it’s super-heavy launch vehicle “Energia,” it degenerated on orbit and accomplished only one flight. Buran completed the first fully automatic landing of a vehicle of its class on November 15, 1988.

На сайте используется обработка cookie файлов. Нажимая на «Да, согласен», вы даёте согласие на их обработку. Ознакомиться с подробностями можно по ссылке